Resonance chambers of contemporary history: clubs between social upheaval and hedonism

Flyer aus der Sammlung des Archivs.

Keynote speech for CLUB CULTURE DAY 2025

by Daniel Schneider (Archive of Youth Cultures)

Clubs are resonance chambers of social developments, mirrors of political upheaval, and retreats for subcultures. In hardly any other city can this close intertwining of history and nightlife be observed as clearly as in Berlin. From the years after World War II through the Cold War to reunification and into the present, Berlin's club culture has always been a seismograph of social change.

Clubs as a mirror of social conditions

This year's Club Culture Day chose the theme “Bridging Realities – 35 Years of Movement” – a deliberate reference to the 35th anniversary of German reunification. In keeping with this theme, Daniel Schneider's contribution highlighted the role of clubs as echo chambers of contemporary history.

His analysis shows that long before the fall of the Berlin Wall, the history of Berlin's club culture was closely linked to the political and social developments in the city. Clubs repeatedly served as mirrors of social conditions and as places where history reverberated on a small scale. Below you can read a revised and abridged version of the keynote speech that Daniel gave on October 3 at the opening event of this year's festival week at the Alte Feuerwache.

No curfew for West Berlin

Berlin was already a divided city in 1949: controlled by the US, Great Britain, and France in the west, and by the Soviet Union in the east. The Cold War had just begun, but the borders were still open and Berliners were largely free to move around; the Wall was not built until 1961.

At that time, West Berlin restaurateur Heinz Zellermayer succeeded in convincing the American city commander to lift the curfew in West Berlin.

This was preceded by a curious competition between East and West for longer opening hours for pubs. Since East Berlin had longer opening hours at the time, many people went there to drink – an early form of inner-city “drinking tourism.” The lifting of the curfew was not only a response to the feared economic losses, but also intended to send a political signal: West Berlin was to be positioned as the “city of freedom” in contrast to the socialist East.

A magnet for subcultures

In the decades that followed, the Cold War continued to shape the city's nightlife in many ways. Soldiers stationed in West Berlin regularly visited bars and clubs, creating an unusually international crowd for German standards at the time. Added to this was Berlin's special situation as a city where, unlike the rest of the FRG, there was no compulsory military service: many young men who wanted to refuse service moved to the city – including artists, activists, and queer people – creating a diverse subcultural milieu.

The cultural scene also benefited from the fact that West Berlin was heavily subsidized for propaganda purposes as a so-called showcase of the West. Even back then, Berlin had an international appeal that attracted stars such as David Bowie, who lived here in Berlin in the late 1970s.

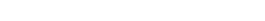

Roxy Palast in Berlin-Friedenau

Credit: Tine Fetz / Places Berlin

In East Berlin, too, the SED regime attempted to present the city as a cosmopolitan metropolis. A key moment was the hosting of the 10th World Festival of Youth in 1973, which contributed to the emergence of a state-sponsored disco culture. However, like many things in the GDR, this culture remained strictly regulated: DJs had to complete official training and, upon graduation, were awarded the title of “state-certified record entertainer” – by the end of the 1980s, there were more than 6,000 of them throughout the GDR. In addition, the so-called 60/40 rule applied, according to which no more than 40 percent of Western music was allowed to be played, a regulation that was often ignored in practice. Discotheques were thus the scene of negotiations between state control and individual freedom. Added to this was the underground scene, such as the punk or goth scene and other subcultures – described by the state as “negative and decadent” – which tried to evade repression and operated informal meeting places. Despite all the restrictions, there was also a lively nightlife in the East.

Clubs as arenas for political conflict

The fact that clubs could be not only places of pleasure but also arenas for political conflict was demonstrated in a particularly tragic way in 1986: three people were killed and around 250 injured in a bomb attack on the LaBelle discotheque in West Berlin. The attack was carried out by the Libyan secret service, which wanted to take revenge for US air strikes on Libya.

LaBelle became the focus of this geopolitical conflict because the discotheque was also frequented by US soldiers, including many African Americans – it was a so-called GI club, where funk, soul and early hip hop were the main genres played. And since the club had a significantly less white audience than many of the trendy new wave and punk venues of the time, it was also popular with people from the Turkish, Arab, and Afro-German communities, among others. Like many other clubs frequented by marginalized groups, it was a kind of safe space for people from these communities until this tragic attack.

Churches as safe spaces

Many churches in East Berlin were also a kind of free space, as they offered people from the GDR opposition movement shelter and protection from repression by the GDR government. But subcultural scenes such as blues musicians and punks were also active within the churches. From the late 1970s onwards, so-called blues masses became established, followed later by rock and punk concerts in church buildings.

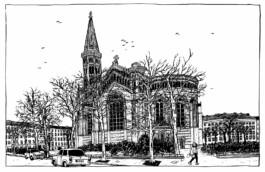

Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg

These places and open spaces offered protection, but they were also targets for attack. In 1987, for example, neo-Nazis attacked a concert by the West Berlin band Element of Crime in Zion Church in Prenzlauer Berg. Several visitors were seriously injured. The attack made it clear that the growing threat posed by neo-Nazis in the GDR could no longer be ignored – a grim harbinger of the wave of right-wing extremist violence in the early 1990s.

The soundtrack of the transition period

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 ushered in a completely new phase of Berlin club culture. In the euphoric atmosphere of change, many creative artists began to occupy vacant buildings in East Berlin and open clubs there. Within a few years, what was initially a small scene developed into a movement of international significance: techno became a symbol of a new attitude to life, and Berlin became one of its global centers.

The new clubs often sprang up in locations that already had an eventful history. The best-known example is Tresor, which opened in 1991. The club was located in the former vault of the Wertheim department store on Leipziger Strasse, once the largest department store in Europe. The company, which belonged to a Jewish family, was expropriated by the Nazis in the 1930s, the huge building was then destroyed in World War II, and the ruins were later demolished. All that remained was the vault, which decades later would become a flagship of Berlin's techno scene.

Leipziger Straße in Berlin-Mitte

Credit: Tine Fetz / Places Berlin

Other club locations, such as the building on Brückenstraße, now home to the Club Commission and the KitKat Club, have a similar past: East German soldiers were stationed here until 1990. The city's history, its fractures and voids, formed the basis for the club culture of the post-reunification era. Without war and division, many of these buildings, which were unused and vacant at the time – we might today refer to them as places of potential – would not have existed.

Techno became the soundtrack of the post-reunification era, and Berlin briefly became an almost utopian place. But other scenes and subcultures such as hip hop and punk also benefited from the special situation, a fact that is often forgotten.

But this new freedom also had its downsides: right-wing extremist violence was also prevalent at the time, but its impact on the club scene has only been researched in fragments so far. It is often said that all social classes and groups came together peacefully in the clubs, but even here there was exclusion and discrimination, and even here there was racism and sexism.

In addition, the euphoria contrasted with the reality of many East Germans. Some of the places where people were now celebrating exuberantly had recently been the workplaces of East Berliners who had lost their jobs and social security as a result of the economic collapse of the GDR—loss and new beginnings were often closely linked here.

Club culture is part of contemporary history

Clubs can be places of refuge and freedom, places of hedonism, but they are never free of social contradictions or unaffected by world events.

Club culture is also part of contemporary history. That is undeniable today. Clubs have always been important to society as a whole; they are socially, culturally, economically, and politically relevant, and they themselves make history. Countless books have been written about Berlin's nightlife in recent decades, there are dozens of documentaries and television series, Berlin's club history is the subject of exhibitions and academic research – the interest is clearly enormous.

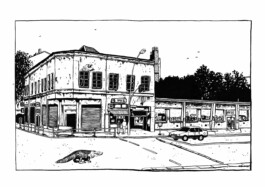

in Berlin-Mitte

At the same time, there are still many gaps in research, for example on the history of GI clubs in West Berlin or disco culture in the GDR. Incidentally, the importance of the history of nightlife and club culture applies not only to Berlin, but also to other cities, as it is a significant and identity-forming part of many people's personal biographies and local history. All of this can give us hope, despite all the crises and conflicts, despite the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, despite the many clubs that have had to close in recent years or are threatened by rising rent and energy costs, because club culture is needed and taken seriously by many people, both in terms of its historical and current social relevance.

Even if the moment, the night, the ecstasy itself cannot be archived, much of what surrounds it can be preserved: promotional materials, flyers, photos, DJ sets, business documents, club decor, or furnishings. The Archive of Youth Cultures in Berlin collects such materials, even the toilet doors of a former club. These documents and objects tell stories that would otherwise be lost, making it possible to understand the social significance of club culture.

The appeal to everyone involved in club culture is therefore: don't throw away your history, but donate it to existing archives or build your own collections. Future generations will thank you for it.

OUR SPONSORS

OUR MEDIA PARTNERS